I read something, and I’ve got things to say about it!

Cryptomancer, “a fantasy role-playing game about hacking”, purchased via drivethrurpg.com as print-on-demand hardcover.

What this is not: Shadowrun in a fantasy setting. Sorry if I just smashed your expectations, but I wanted to get that out of the way. So, what is this, then? Glad you asked.

Cryptomancer is a fantasy RPG with mechanics for instantaneous, but not inherently secure communication using crystal shards and the innate-to-all magical ability to work cryptomancy, a magic form of cryptography. You wont roll on hacking, though.

The Setting

The Setting, a very vaguely defined fantasy world to be filled by the group or the GM, is inhabited by three major playable races.

Obviously those are humans, elves and dwarves, because genre.

However, while the humans are generally the common, run-of-the-mill diverse background population they always are, elves and dwarves come with some twist.

The dwarves of old might have been a proud and strong axe wielding warrior race, but from days of yore only their talent for tinkering remains. The dwarves today, while still organized in clans, gave up open warfare long ago for petty squabble and one-upmanship, and while territory still is worth something – if only because of trade routes – two clans might as well quarrel over the right to some inventions or fight an economic or industrial war. Not all dwarves went with the times, however, and those who still wish for a return of the glorious days long gone are usually easily identifiable by their long beards…

The elves went from one-with-nature-treehuggers to a state-scale narcotics operation, happily sacrificing forest by the square mile to the production of soma, the drug of choice in The Setting. Harvested from a special type of bug inside a tree that hijacks the tree and destroys the surrounding forest by out-competing everything else for water and nutrients.

There are also the Risk Eaters, Cryptomancers world-spanning conspiracy, toiling away in the dark, running huge analytical engines, trying to find and eliminate threats to the world-as-we-know-it before they even emerge. As you might have guessed, the player characters run across this faction by design. Also, it is not necessary for the players to actively cross them or to even know about them: they are there, and their computers told them the group is a risk, so they act upon it.

The one setting given in the rule book is on the border of Sphere, the lands of the humans, and Sylvetica, the elven lands, with the humans constantly battling against the forest that constantly tries to swallow everything. Needless to say, the forest is pretty damn dangerous. Subterra, the dwarven realm, come into play through tunnels, caverns and – of course – mountains.

However, the book explicitly states that this is only a small part of the world, chosen for the obvious conflict potential on the three-realm-border: given the broad-purpose rule set and the game’s heavy reliance on narrative, a change of place is only hampered by a group’s lack of imagination.

The shards, the crystals providing The Setting with its most important method of communication, came from space. On their way they obliterated a number of small kingdoms and left one giant block of obsidian and countless smaller, clearer shards. The black block can be cut down to roughly the size of a melon and provide communication with every other of its kind, building the Shardnet. The other kind can be cut down to fist-sized blocks, providing a shared network between all shards from the same source stone.

Last, but certainly not least, the cryptomancy. The innate magical ability to do cryptography… in your head. Or rather the magic part of your head. Or something.

Available are symmetric and asymmetric cryptomancy. The former is based on agreed-upon keyphrases, the latter uses a persons unique true name as the public and the persons soul as private key.

As all true names are unique, anything encrypted with the persons true name can only be decrypted with the corresponding soul, and vice versa.

Symmetric encryption is automatically decrypted by anyone who has ever read or heard the keyphrase used for encryption, forcing the use of creative use of language. Using total garble is difficult as the phrase must be spoken to get the encryption going. Decryption, as stated before, happens automatically if the PC has ever noted the key. I balked quite a bit on the thought of the wetware automatically brute-forcing encryption, but then… it’s magic. Roll with it.

Major elements of the game are proper operation security (OPSEC, aka “don’t talk too loud in the tavern about your plan to raid the bank”), proper handling of cryptographymancy (keyhandling, key distribution, comms discipline) and how to exploit other actors’ failures in these fields.

The Characters

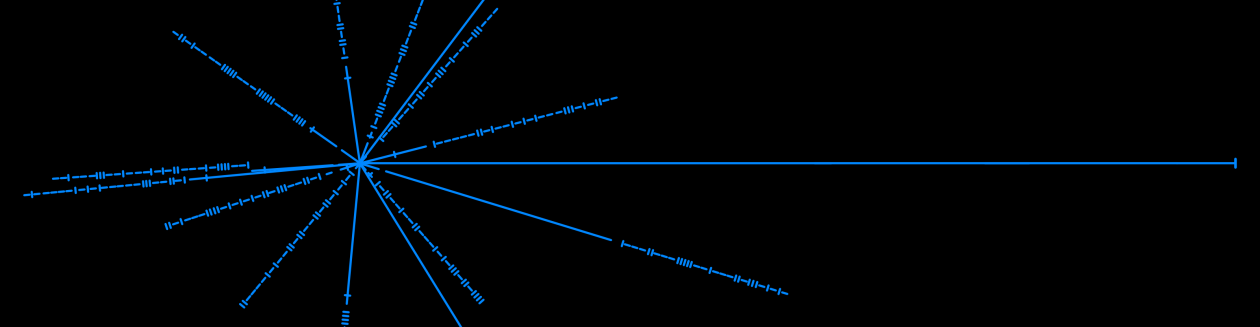

Here’s a character sheet.

Common name, true name, sex/age/race and name of the party should be somewhat self-explanatory.

Next to that, characters are governed by qualities in appearance and personality. Little descriptions helping the flesh out of the character, with no “hard” impact on the game.

Of the attributes, there are four (Wits, Resolve, Speed and Power), each governing either 4+4 skills or 4 skills and willpower (Resolve) or endurance (Power). Skills are what is usually rolled upon (see The Rules below), covering certain areas of expertise – e.g. “precise melee” is everything from dagger to rapier or anything else allowing for precise wounding, while “brute melee” covers less precise hitting implements: swords, axes, warhammers…

Trademarks weapon and outfit are, well, the character’s trademark weapon and outfit – you usually wont carry an arsenal around, at least not by design.

Then there are certain Talents, making life easier. Following established paths, talents cover a broad field of things: Bonecrusher, Attractive and Highbred for example are all counted as talents.

Spells, as no-one could have guessed, are just that. However, any character can learn spells (as well as fighting talents) – there are no character classes, it’s all a matter of time invested.

Next to the player characters, the other important persona in the lovely little mess that inevitable is going to happen is the PCs’ safehouse, provided (usually) by Mr. Johnson. Yeah, okay. It is provided by the party’s patron, and the authors missed the opportunity to canonically pull a shadowrun and name all patrons ever Mr. Johnson. Back to business.

The safehouse has its own character sheet and can accommodate several improvements, making specific tasks easier. Take a look, it’s wirtten on there. Improvement, same as cells, are purchased by strategic assets, given to the group by their patron for jobs well done. Cells, best transition ever, are specialised groups of subcontractors ranging from assassins and smugglers all the way to shardscape-specific professions like codebreakers or quite literally DDOS-bots. They come in more and less punch and corresponding less or more deniability. It’s all about OPSEC, after all.

The Rules

So far, I’ve had no opportunity to playtest this thing, so all commentary is solely based on thoughts upon reading.

The rules are quite simple and follow the general broad-strokes-design of the game. As mentioned earlier, there are not too many character stats, and three basic difficulties defining the number needed to be rolled on an attribute die to score a success.

For a skill check, five die are rolled: the corresponding attribute dice, d10, and as many fate dice, d6, necessary to get to five. On an attribute die, a 1 is a success-cancelling botch and everything above the target difficulty is a success – on a fate die, both a 1 and a 2 are botch and a 6 is always a success. It is possible to get out of trouble relying on fate, but using skill is by far more reliable. All in all, the system looks quite solid.

There are the usual opposed and unopposed checks for situations of active competition or not, as well as a mechanic for group members to support each other on a check.

The game is generally divided in scenes and downtime, the former being time when active play takes place, the latter being eight-hour-periods in which long-time tasks like crafting, alchemy, and even elaborate social interaction (“I have to mingle for some hours at the market to somehow get a lead on whom to ask the REAL questions”, “I’ll be spending the day at court, trying to leave a favourable impression”) you don’t want to play out in every detail can happen.

Downtime spent in a safe location is safe, downtime spent anywhere else triggers a risk roll.

Which brings us to risk, an ever-increasing party wide stat, tracking the, well, risk of an attack by the Risk Eaters.

Risk goes up about every a player decides to defy fate (moving one step up on the success-scale, e.g. turning a botch into a success) or the party violates proper OPSEC (by discretion of the GM), and every time the party takes a downtime in an insecure location (e.g. resting in the wilderness), a d100 is rolled. If the result is lower than the current risk rating, a Risk Eater-attack is triggered. They always sent highest caliber assassins (in fact, canon-wise all Rise Eater-cells consist of highest caliber… people in general), and they send more each time the risk roll hits.

I have seen less in-the-face player-killing mechanics, and it is something I think will end up modified after a test run. But I’d need to run a game or three before making a final say there.

Addendum: some assumptions given rules seem quite… far-fetched, like “no-one and nothing would ever attack a mount, only ever the rider” or “a typical group of mercenaries can not only out-fight, but also out-socialize and out-investigate the players”, but that’s for every group to decide whether or not these are ok assumptions.

The Book

The print-on-demand hardcover I call my own is okay.

The cover is solid and well done, the print is clear, but the whole thing suffers from white printer stripes on large surfaces and some pages were not cut correctly, resulting in a white stripe between the edge and the deco-print-side-stripe-whatever.

The paper quality is not cutting edge but okay.

All in all, it really is okay. Also, I like the cover art.

The game is also available as pdf of good quality.

The Conclusion

This game holds interesting ideas and provides an interesting setting – how well it works in a real session remains to be seen. As stated at the beginning, it is not a ShadowRun IN SPACE IN FANTASY, but gives a for all I know unique setting with a good in-universe explanation for no-latency long-distance communication. The lightweight rules allow for fast and simple resolution of conflict without devolving into lengthy sessions of rolling dice, and the minimal world design allows for easy accommodation of the desired settings.

It is not what I expected (a system with a WAY deeper rule system to accommodate finer points of cryptography), but I’m nonetheless curious to see how this works in actual play. And as soon as I manage to get a session going, I’ll let you know how it went.